All of us should hope that Mitt Romney’s shooing takes place sooner rather than later.

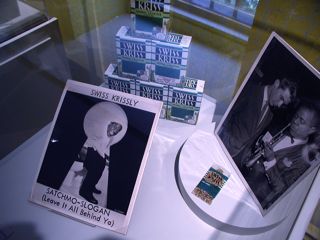

Letters of Note: Music is Life Itself

Here’s a link of note: Louis Armstrong’s 1967 letter to a Marine stationed in Vietnam. Louis was big into the Swiss Kriss — and music, of course. The picture here is the Swiss Kriss display at the Louis Armstrong House in Queens, New York. Link: Letters of Note: Music is life itself [@archive.org].

All the Lack of Posts

Sometimes, if you’ve spent enough time without a new post, it’s necessary to offer some sort of explanation, some reasonable story as to why you haven’t updated your website in so long. Or, maybe it isn’t necessary. It’s just possible that no one actually cares one way or the other, particularly if no ipo is forthcoming. In any case, let’s just say that various kinds of life events have interfered with the process and caused various kinds of distraction. One such event is shown in the picture here, the “coach” character at a recent St. Paul Saints exhibition game. He lead us all in exercises between innings, feigned irritation with the Saints mascot “Madonna” (also pictured), and wore what appeared to be a fake mustache.

Maybe the real problem, ie., what caused “lack of post syndrome,” was all the tree pollen in the month of April.

Roswell Rudd Records An Album Of Standards by Roswell Rudd — Kickstarter

The trombonist Roswell Rudd is up to a new project: recording an album of standards. Help Mr. Rudd out by visiting the link below and adding your bit of support.

Roswell Rudd Records An Album Of Standards by Roswell Rudd — Kickstarter.

Yamaha Slide Oil

I’ve been using it since summer last, and Yamaha Slide Oil does a fine job of lubricating my trombone slide. But — no doubt like many people — I sometimes get concerned about the possible toxicity of substances I use on a regular basis. This slide “oil” (actually a soapy-looking concoction), works great, but what’s in it? I couldn’t find the information on the internet, even on Yamaha’s own website. They did have a web form for inquiries, so I wrote in:

Hello:

My question is about Yamaha Slide Oil — is it possible to list its ingredients? I’m interested in the oil’s relative toxicity to humans. Thanks, Chris

In a while, I received an email from a helpful product manager at Yamaha. He included a fairly standard Material Data Safety Sheet. To cut right to the chase, Yamaha Slide Oil doesn’t contain anything that is an eye, skin, or inhalation irritant. Although practically non-toxic, Yamaha Slide Oil should not be ingested because doing so could give you abdominal cramps and diarrhea. Insert you own TV dinner and/or Hot Pockets joke here.

The basic ingredients found in Yamaha Slide Oil:

- Stearic Acid

- Oleic Acid

- Palmitic Acid

- Ethylene Glycol

- Silicone Oil

- Anti Corrosion Reagent

- Water

05/26/23 5:28 PM: A more recent revision of the data sheet for Yamaha Trombone Slide Lubricant can be found here.